“How big is it?”

You need 3 center fielders to cover all the ground out there

Okay, as a joke it’s awful, but it is a common statement amongst Tigers fans. At the very least the belief is that multiple center fielder type players are required to man left and center fields. When you look at the massive expanse of green, it certainly seems believable. But when I go through the game rolodex in my head, I don’t recall an inordinate number of balls landing in the left-center gap. Center field is a massive piece of real estate, but since the ball park was reconfigured left field seems quite manageable. Does Comerica really play as big as it’s reputation in left and center fields?

Probably the best way to tackle this is in terms of park factor. As a refresher, park factors look at how a team and its opponents perform in said team’s home ball park, and then divide that by how the team and its opponents play on the road. A value of 1 means that a park is neutral. As a point of illustration the Tigers and their opponents hit 59 triples in Comerica Park this year. On the road the Tigers and their opponents combined for 37 triples. So 59 divided by 37 is 1.60 meaning it was 60% easier to hit a triple in Comerica than a typical stadium last year.

Now that the park factor primer is out of the way, let’s look more at Comerica. We know that traditionally Comerica Park suppresses homers. The Bill James Handbook has the park at .94 for 2005 through 2007. And that is despite an uncharacteristic 1.14 rating this year. But we care a little bit less about homers for this exercise. While it is a demonstration of the park’s size, it doesn’t really speak to what type of outfielders are needed because those balls (for the most part) aren’t fieldable anyways.

The first thing I wanted to do was get a handle on how many balls were dropping in for hits and where. To do this I used retrosheet data and borrowed a methodology being developed by Dan Fox at Baseball Prospectus. While retrosheet doesn’t have specific hit locations, it does indicate who fielded each ball. So I looked at the hits and the outs to find out the rate that balls were converted to outs in left, center, and right fields.

Essentially what I ended up with was a modified batting average on balls in play. For each “field” I looked only at the non-grounders and calculated how many resulted in baserunners. I excluded grounders at this point because with the exception of freakish plays, outfielders aren’t just going to be able to convert those plays to outs no matter how skilled they are.

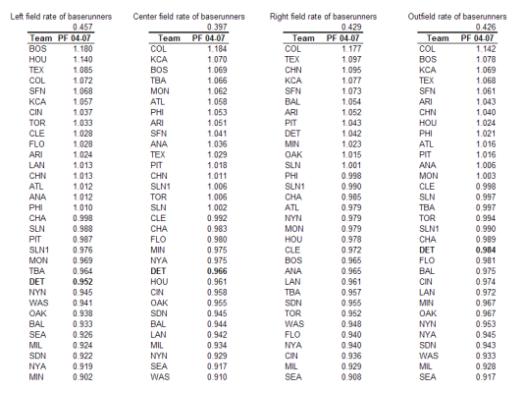

I did this for each field and each stadium and I did it across data from 2004 to 2007. I used 4 years because park factors can be volatile, and because more data is usually better than less. Especially when you start to break down the data into smaller components. The overall rates for this modified BABIP, I’ll call it oaBABIP were:

- Left Field: .457

- Center Field: .397

- Right Field: .429

The tables below show the park factors for each park over the last 4 years. SLN is old Busch Stadium and SLN1 is New Busch Stadium. (click the image for a bigger version)

Boston’s Green Monster looms over left field, and left field data as well with many would be outs banging off the wall. As for Comerica Park, fewer balls drop in for hits in left and center fields in Detroit than in other parks. Right field, which is the much less talked about field here in Detroit, is actually a more favorable hitting field. Overall, despite Comerica’s spaciousness slightly fewer balls drop in than the typical ball park.

So at least in terms of balls dropping for hits, Comerica doesn’t seem to present an additional challenge for it’s outfielders. Of course the rate of hits is only part of the story. In the next part of this series (okay, it’s probably a series of 2, but a series nonetheless) will look at the impact of extra base hits.

For more on the subject, I invite you to check out Mitchel Lichtman – The Hardball Times – Speed and Defense in which checks to see if fast players benefit from playing in large parks defensively, and if the plodders do well in small parks. And if you’re a Baseball Prospectus premium subscriber check out the aforementioned Dan Fox – Baseball Prospectus – Defense and Alphabet Soup

UPDATE: Here is part 2

The information used here was obtained free of charge from and is copyrighted by Retrosheet. Interested parties may contact Retrosheet at www.retrosheet.org.

Excellent post Bill. Maybe we should not be surprised when seemingly mediocre left fielders put up good range numbers as they have in recent years. I’d be interested to see the data specifically for line drives because everybody always says it’s a great park for line drive gap hitters.

Lee

Another great analysis. I feel like I learn something new every time I visit DTW. Great stuff!

All parks have the same size gaps in that the two foul lines vector out at the same right angle. Thus, outfielders playing at 350 feet out would have the same gap of space between them regardless of park. If the outfielders play deeper because of the depth of the field, say 375 feet, the gaps between the outfielders would increase but the time to get to the ball would also increase negating some of the gap effect that a deep outfield has. What should change more dramatically in a park with a deep outfield is the gap between the infielders and outfielders. Infielders position themselves the same with little respect to park dimensions. Outfielders moving back 20 feet in a deep outfield are going to be 20 feet further away from the infielders and 20 feet further away from any ball dropping in front of them and as a result singles and hustling doubles should increase.

Another effect of a deep park is that balls that do make it through the gap are going to go farther favoring triples and stand-up doubles.